Nicene Creed, One Word Changes Everything

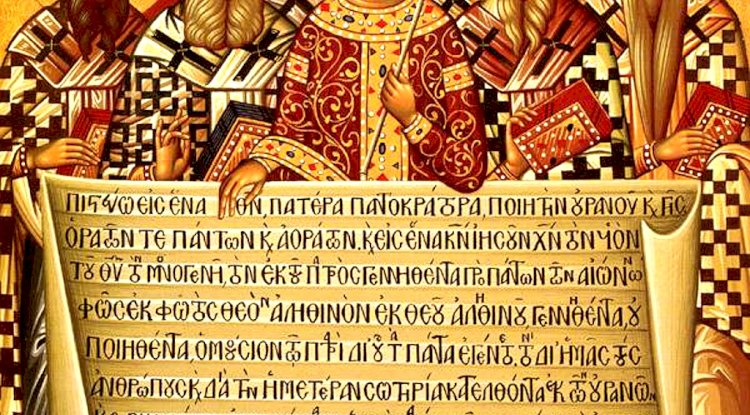

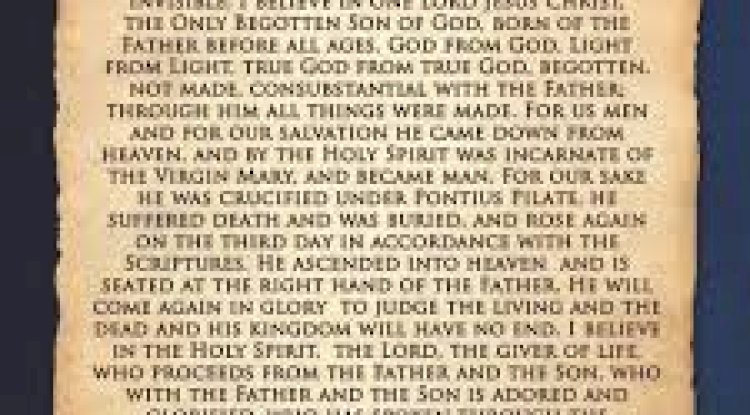

The Creed finally promulgated by the Council of Nicaea was a rather awkward fusion of bits and pieces from the local baptismal confessions of churches in the Eastern Mediterranean with some new phrases aimed at clarifying one central and all-important problem.

Very briefly, the problem was this: no one seriously thought Jesus was no more than a human being; but exactly what kind of non-human power or agency did he embody?

Earlier generations had used language which might imply that he was the human avatar of a great archangelic presence in heaven, a heavenly high priest leading the eternal angelic liturgy. Other idioms and images built on the biblical idea of Jesus as the human expression of God’s eternal Wisdom and “Logos” – a life completely in tune with the mind and will of God; but it was less than clear that this eternal divine mind could be thought of as a real everlasting “subject”, the eternal Son of the eternal Father.

The bishops at Nicaea decided to express the absolute inseparability of this non-human heavenly agency from the life of God the Father by using the controversial word homoousios: “consubstantial”, “of the same sort of being”. What was embodied in and active in Jesus was nothing less than the life of the one creator of the universe. But that life was from all eternity a life of relationship and gift.

God the Father was eternally sharing his life with an eternal Other, an Other who received this self-giving love and returned it. God never began to love or to share the divine life; “before all ages”, beyond the history of God’s involvement with creation, God is this kind of God. He never needs to be persuaded to love or give or to be faithful and generous; he just is these things. His divine unity is not a mathematical singleness but the unity of a single loving act flowing, returning, overflowing once again. St Thomas Aquinas, writing about this, quotes St Bernard’s statement that the highest imaginable form of unity is this unity of interactive communion, not the life of some abstract and solitary individual in heaven.

So the Creed begins by affirming that there is one and only one God, source of all things, and that this one God is a “generating” God, a “Father”, who without interruption brings the Son to birth. He doesn’t create this second subject by an act of free will. This is how he just is. So we believe also in one “Lord”, the one who comes to us and transforms us in the life of Jesus. In the earliest text of the Creed, we’re told that this Lord is “begotten” – “generated” or “birthed” would also work as translations – “out of the substance of the Father”. So the eternal Son is not composed out of anything but the life of God.

The Creed uses an analogy already venerable by the time it was written – “Light from Light”: a flame or a lamp pours out its light without losing anything of itself; the light is continuous with the flame. And another flame kindled from the first light is again in complete continuity with it. The word “substance” here is not really meant to be a technical term (and tidying up the technical vocabulary was to take the best efforts of theologians for most of the next century). It’s best to see it as a way of saying “Whatever is true about what makes God to be God is true of the Son, the Logos, the Word, that is made flesh in Jesus; that action and power is no less than the power of the one creator.”

And so to the word homoousios. It had been used by some earlier theologians to express the unity of Father and Son, sometimes comparing the relation to that between flame and light or, say, water and steam. Here is the same reality generating something that is in some way new and different. But the word had several other meanings in philosophy at the time. It could mean two examples of the same kind of thing, or two different things making up a compound reality; and neither of those would quite do for the relation of Father and Son in divine life.

Quite a lot of bishops had second thoughts about whether it was the right word to use. But during the fourth century, theologians like St Athanasius and St Gregory of Nyssa put enormous effort into defining the sense in which the word was being used, and it was increasingly seen as the only secure way of avoiding any idea that the Word of God (as described at the beginning of St John’s Gospel) was any kind of afterthought, any kind of optional extra in the life of God.

There is the main point. It is not an “afterthought” for God to be love; loving is not something God may or may not feel like. God is everlastingly the giver of life in relation, the life we know as adopted children of the Father. And we grow into that life through the gift of the Son who calls us to share his everlasting, “consubstantial” intimacy with the Father, through the indwelling of the Holy Spirit.

What's Your Reaction?